In the late 80s, I decided to spend serious money on my first serious synthesizer. Unfortunately, I did not have any money, so I started scouting the ads and mailing lists of lot sellers. There was this one company that, obviously, had good connections to the dying Italian synth industry, and I clearly remember the magnificent Elka Synthex on top of one of those leaflets, a true monster of an analog synth, somewhere on the path between “hopelessly old-fashioned” and “awed classic”, on sale for just over 3000 Deutsche Mark, if I remember it correctly.

I ended up spending 1500 Marks on another Italian Synth: The Keytek CTS-2000 from Siel, later bought by Gibson, even later bought by Roland just to close them down. [Update, 28-May-17: Interesting additional info about what became of Siel after the Keytek is to be found in the comment by microbug.]

1987 ad for the Keytek CTS-2000 via RetroSynthAds – linked

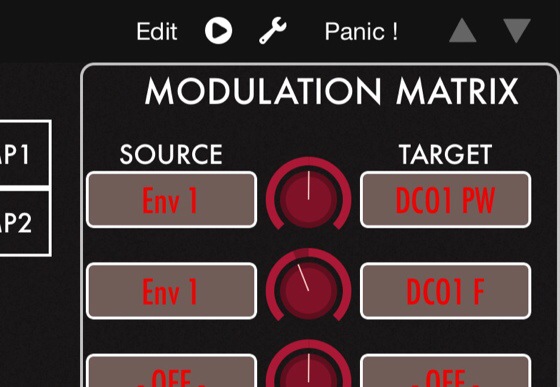

From today’s perspective, this machine was not much of an improvement over my previous means of sound generation, the Casio CZ-101, a digital synth with its very own character. But then, the CZ seemed unbearably cheap and nonsensical to me, with its small keyboard, and its four-voice limit. The CTS-2000, on the other hand, was an eight-voice affair with a proper, velocity-sensitive keyboard. And the technology! Sampled waves! Dynamic wave manipulation! Multitimbrality! Sliders for real-time parameter control! Six-stage envelope generators! And! Analog!! Filters!!!

A great concept. There was, to quote another classic from the era, just one tiny little flaw.

There were a few questionable decisions made in the design, as you can read here. It also lacked the processing power to do what it tried to achieve; its TMS-7002 brain was too weak. But the worst thing was: The synth sounded horrible. What I had hoped for was classic analog punch with a digital, modern twist. What I got was a dull third-rate ROMpler. One of the best sounds was no analog pad but a sampled ripoff of a DX-7 slap bass sound. Despite its analog filters, the sounds were thin and harsh, and even the metallic sounds did not shine but came across flat and dull. All high frequencies seemed to be missing.

Dull by design – the central flaw

I tried to make up for the lack of overtones by buying a small enhancer, a device meant to generating additional overtones, and it sort of helped with the piano sounds. But the overall sound remained disappointing, and later, I realised what the problem was: the output circuitry dulled down the sound. A crude and uninteresting low-pass filter removed all signs of life from the signal.

Thinking about it, this is due to the limited technology. When you work with samples, you get quantization noise – the difference between the original wave and the wave generated with, say, an 8-bit resolution. [EDIT: Thanks to a comment by Mikkel Karlsen I learned that the Keytek was built around two SGS M114A chips, digital oscillators based on wavetable ROM, and I suspect that they were used with the lowest possible resolutions of 16 steps per wave cycle, so you would actually get Q-noise three octaves above the pitch frequency of the wave.] Quantisation noise is noise with the frequency of the sample playback, meaning that with lower sampling frequencies, say, around 10kHz, you will get an audible hiss in the signal. But the feeble hardware is incapable of high sampling frequencies. Think of it as a permant, built-in bitcrusher.

The designer seem to have feared that noise, so they added the low-pass filter to the outputs. I actually quite liked it, so I removed a capacitor from the circuit and killed the filter. It sounded a lot better to me after that.

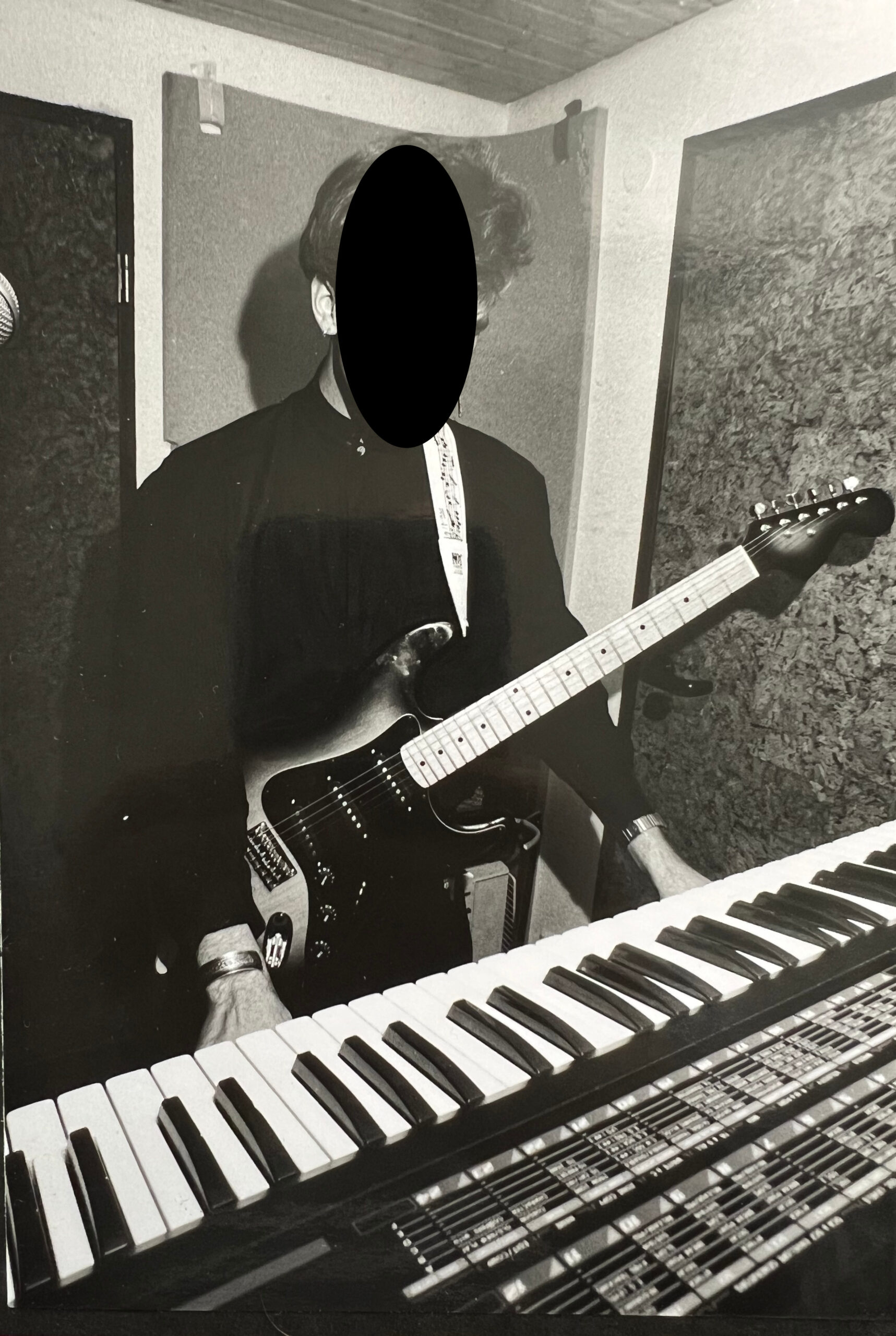

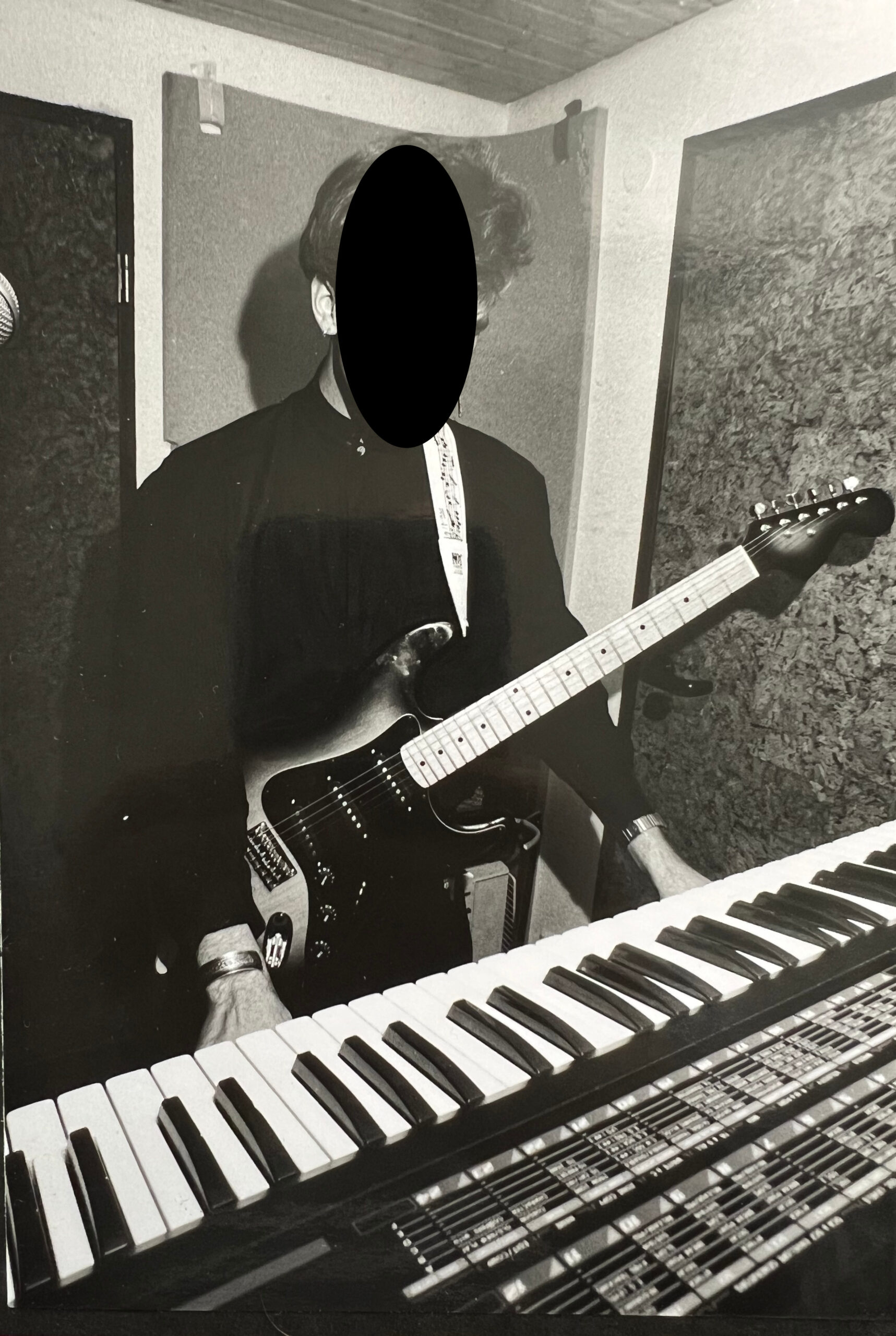

It’s October 2024, and I just discovered a couple of photos proving that I actually played that thing.

Moving on

Still, the Keytek remained an uninspiring machine – and I was really glad to sell it and to move on to a really decent FM synth, the Casio VZ-1. (You see, I’ve got a soft spot for underdogs.) And all the analog warmth I’d ever need soon came from my Matrix-1000 – the one that only recently has undergone brain surgery. And the CTS-2000 went, never to return.

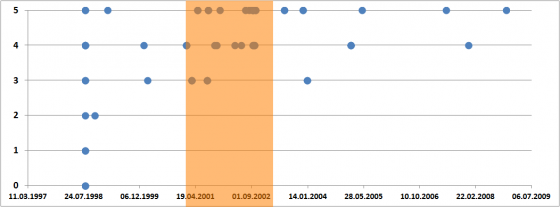

I had all but forgotten the Keytek, but rediscovered it while doing a lot of research on the Matrix 1000’s peers, the generation eventually killed of by the DX-7 and the D-50: 8-bit machines with an analog heart like the Polysix or the Elka EK-22 (another machine that I could have ended up with, and that would have made me much, much happier). These machines keep intriguing me, and although there is quite a good argument to be made that they were closer to what we search in creating sounds – I urge you to read Bob Weigel’s thoughts on the age of Analog and how it ended – I guess it’s just nostalgia, a longing for the time when the world was great and the technology was a marvel.

So I’m remembering the Keytek with fondness and a lot of sympathy for its engineers. I would never take it back, though – even nostalgia has its undisputable limits.

Nice. New. Toy.

Nice. New. Toy.