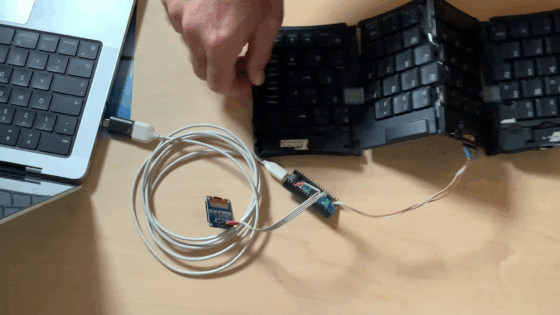

A small project to reconnect an old Targus Stowaway Handspring keyboard with the modern computer world, and learn some more Raspi Pico Python in the process.

Category Archives: Basteln

Internal Speakers Mod: Can I hack my Yamaha Reface to sound as least as good as my Macbook?

To start with the bad news: The answer is probably no. (Betteridge’s Law holds.) But it may be good to know that there are possible options for an internal upgrade of the Reface speakers, and that the Reface speakers aren’t really that bad (albeit tiny). So please stay with me.

Some love for the Playstation 3

The PS3 is amazing – I got it 16 years ago, and it’s still running, working as a Blu-Ray player, and for the occasional round of Little Big Planet with the kids. And Sony still sends updates! But I noticed the fan has been getting rather loud, so I guessed it was time to clean the cooling paths.

In the end, it took me about 30 minutes to take it apart and put it back together again, due to Sony’s service-friendly design. And it wasn’t quite as bady in need of some cleaning as I feared.

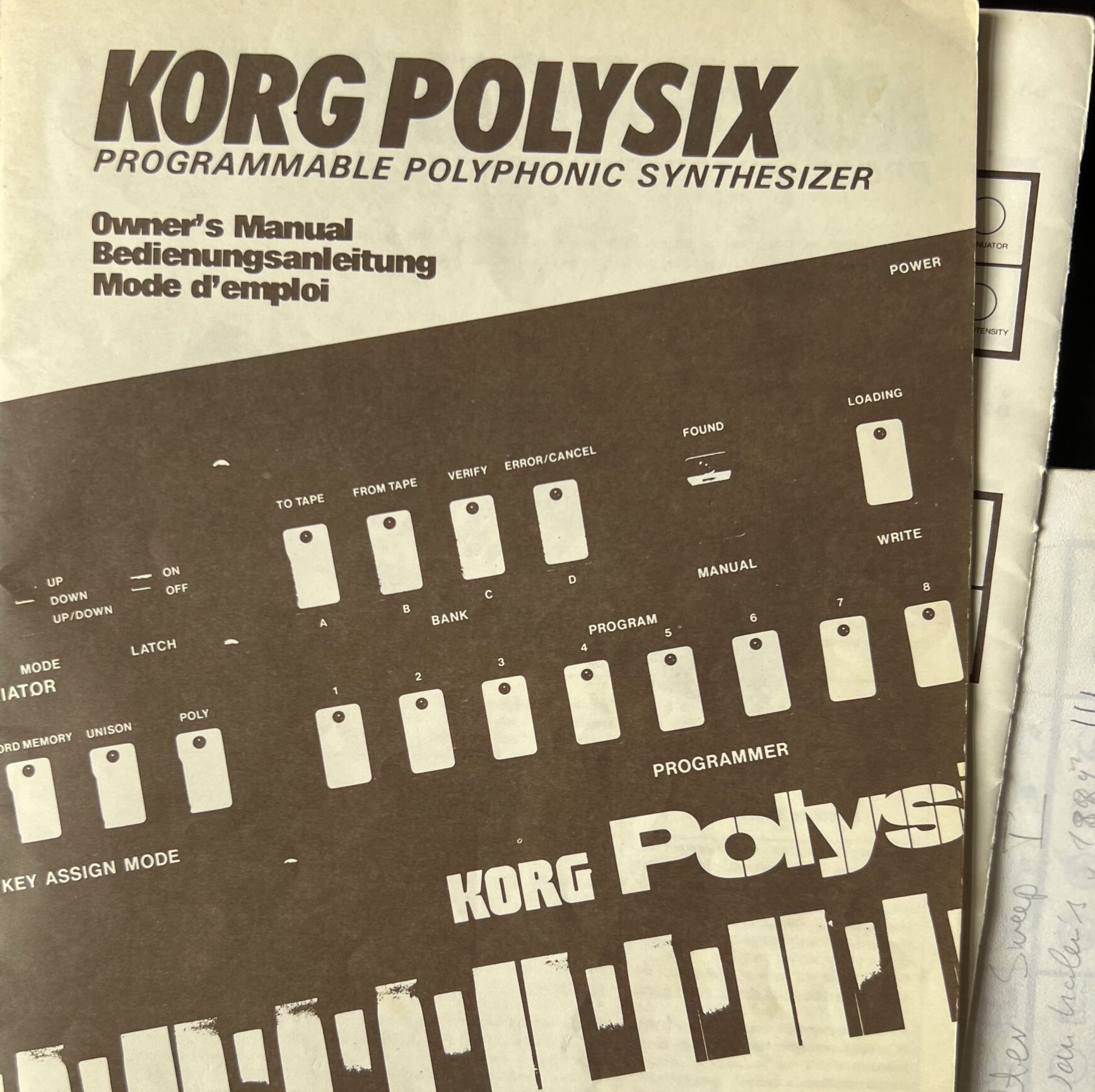

Fixing a Korg Polysix. A Polysix!

Getting hold of a piece of synth history, and a piece of my own history as well. And fixing it is just like everybody tells you it is.

Thermomix TM21 electronics: Speed knob maintenance

(I wasn’t willing to translate that myself; GPT-4 generated translation. German original here.)

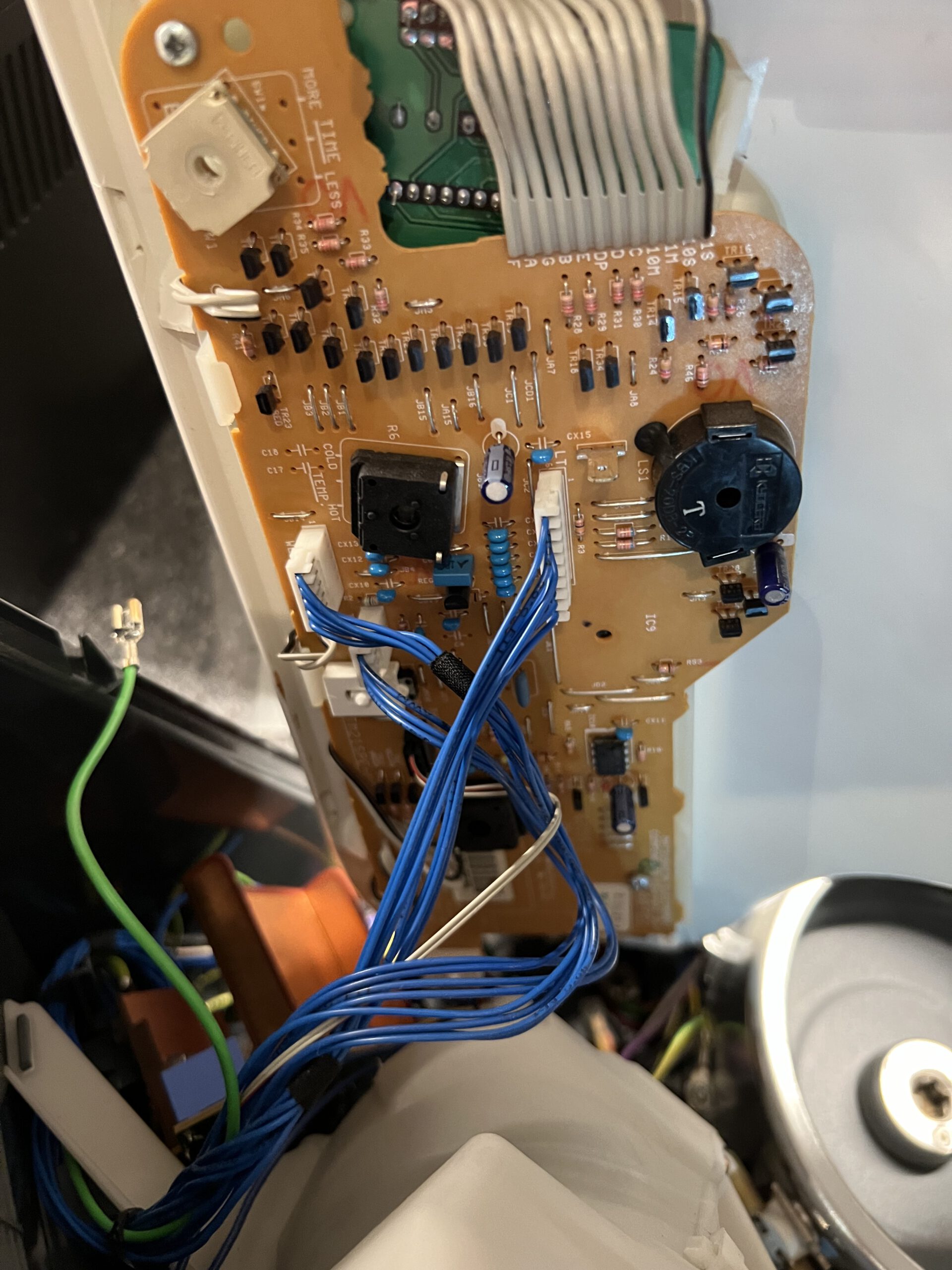

Unhooking and Folding Away the Upper Casing Shell

Next step is to unhook and fold away the upper casing shell. Disconnect the cables from the electronics – there are three white flat connectors with blue wires in different sizes, one black (with two grey cable cores), and the contact shoe of the green grounding wire. Once these are disconnected, you can remove the entire upper shell from the device.

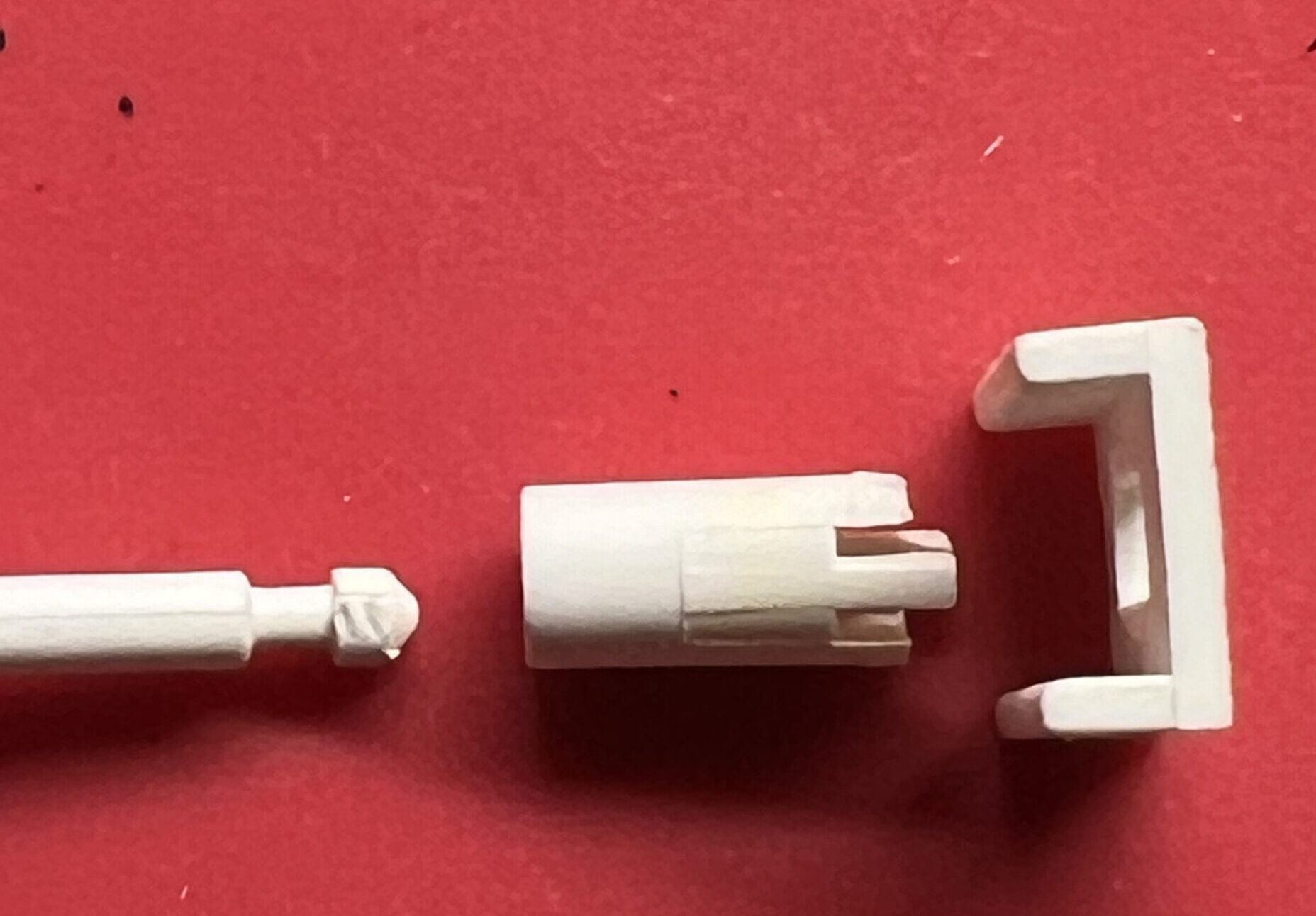

Buggered those Push Buttons!

These can be tricky. That’s why it’s a good idea to watch a tutorial first.

Understanding the Push Buttons Mechanism

The push buttons are comprised of two main parts: the actual button, which protrudes from the front of the casing with a pin attached to it, and a counterpart that keeps the switch contact closed as long as no one presses the button. To remove the button, you need to detach the top part from the pin. That much is clear.

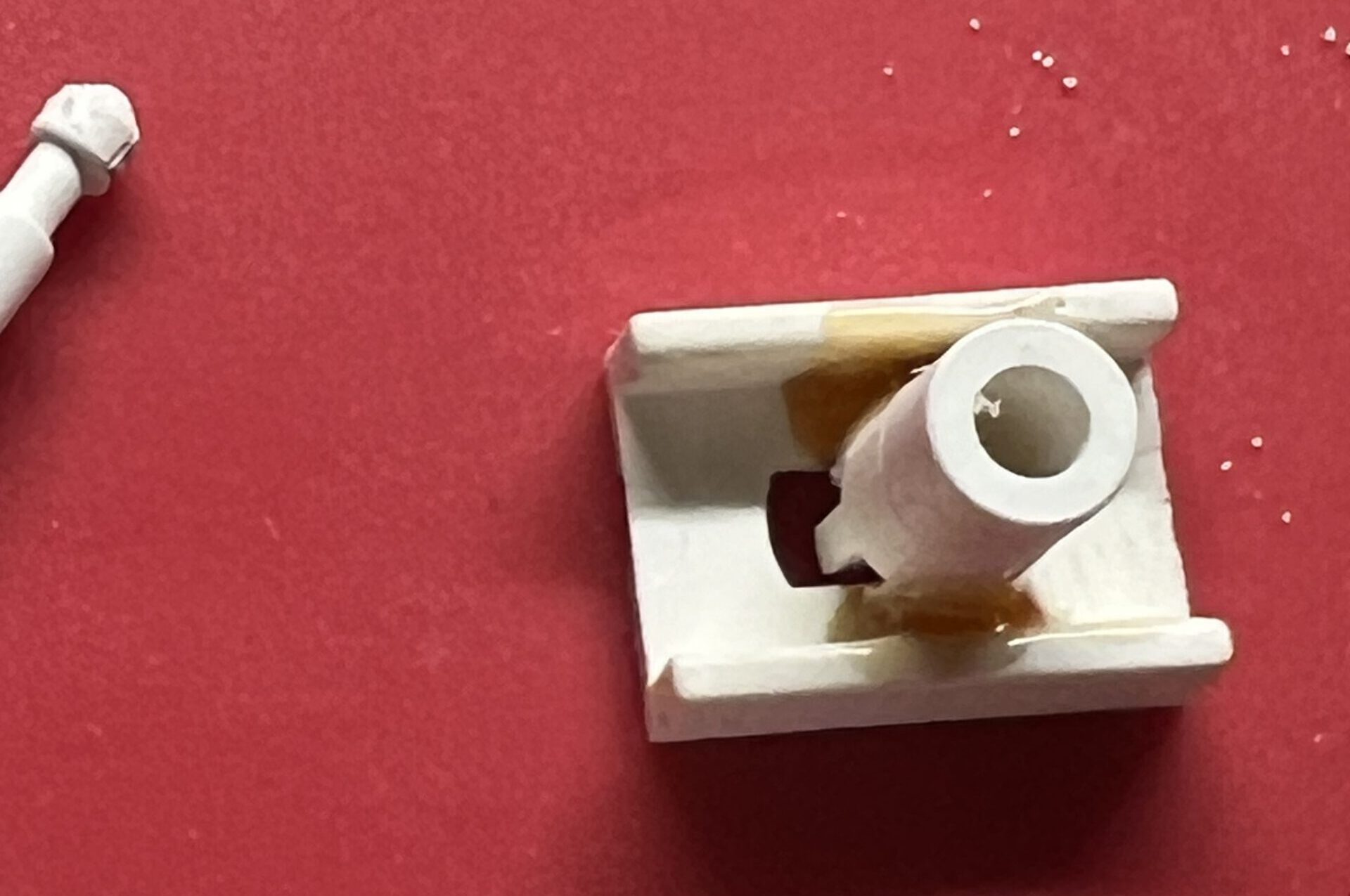

Unfortunately, the only solution I could think of was to use force, which led to me tearing off the rectangular plate on top. (This plate presses the switch.) It’s flanged to a tube where the pin goes, and at its upper end – visible through the slit below the plate – there are two small arms that hold the pin. You need to spread them apart using two small watchmaker’s screwdrivers, then you might be able to pull out the pin. Maybe.

Or, it might end up looking like this – the part in the middle and the one on the right are actually supposed to be connected; I ended up brutally tearing them apart.

I resorted to the reliable two-component adhesive. It worked after reassembling, and I hope it holds permanently, though I’m not very confident. If I can’t find replacement parts, maybe I’ll 3D print them, or else I might just permanently attach the plate to the pin.

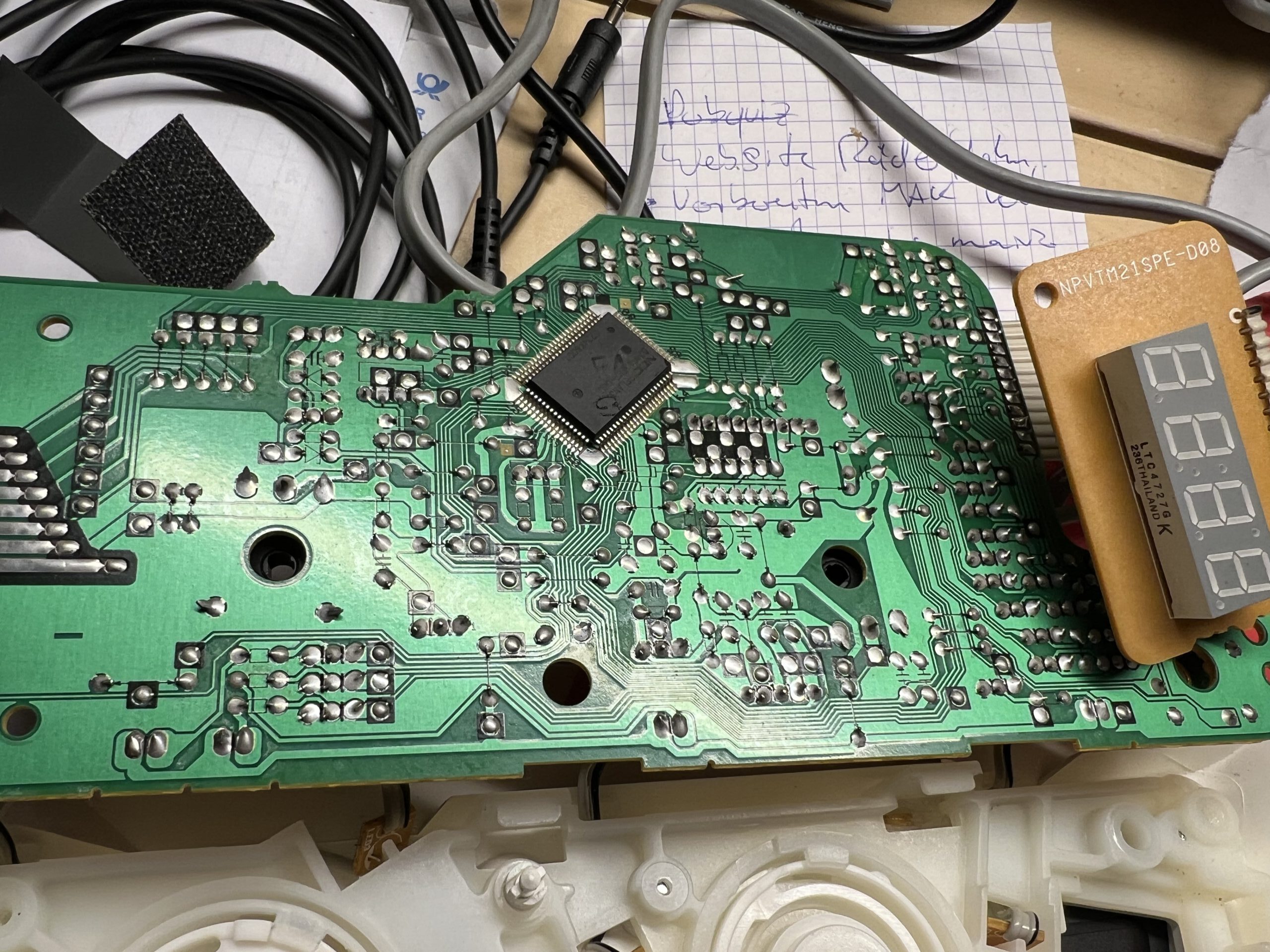

Next, unscrew the three screws from the circuit board and unhook the display, which is held in place by two plastic tabs. Then, remove the electronics.

The potentiometers are soldered at three contacts as usual and additionally held by two tabs that are inserted through the housing and bent over. Carefully unbend these, lift the three poles of the potentiometer, and remove it.

It’s a 22k potentiometer from Piher. I couldn’t find a replacement part quickly, so I decided to open it up. (Update: I’m trying with a Pipher PT15NH now; that’s the closest approximation I could find with that through-hole shaft. Piper datasheet here.)

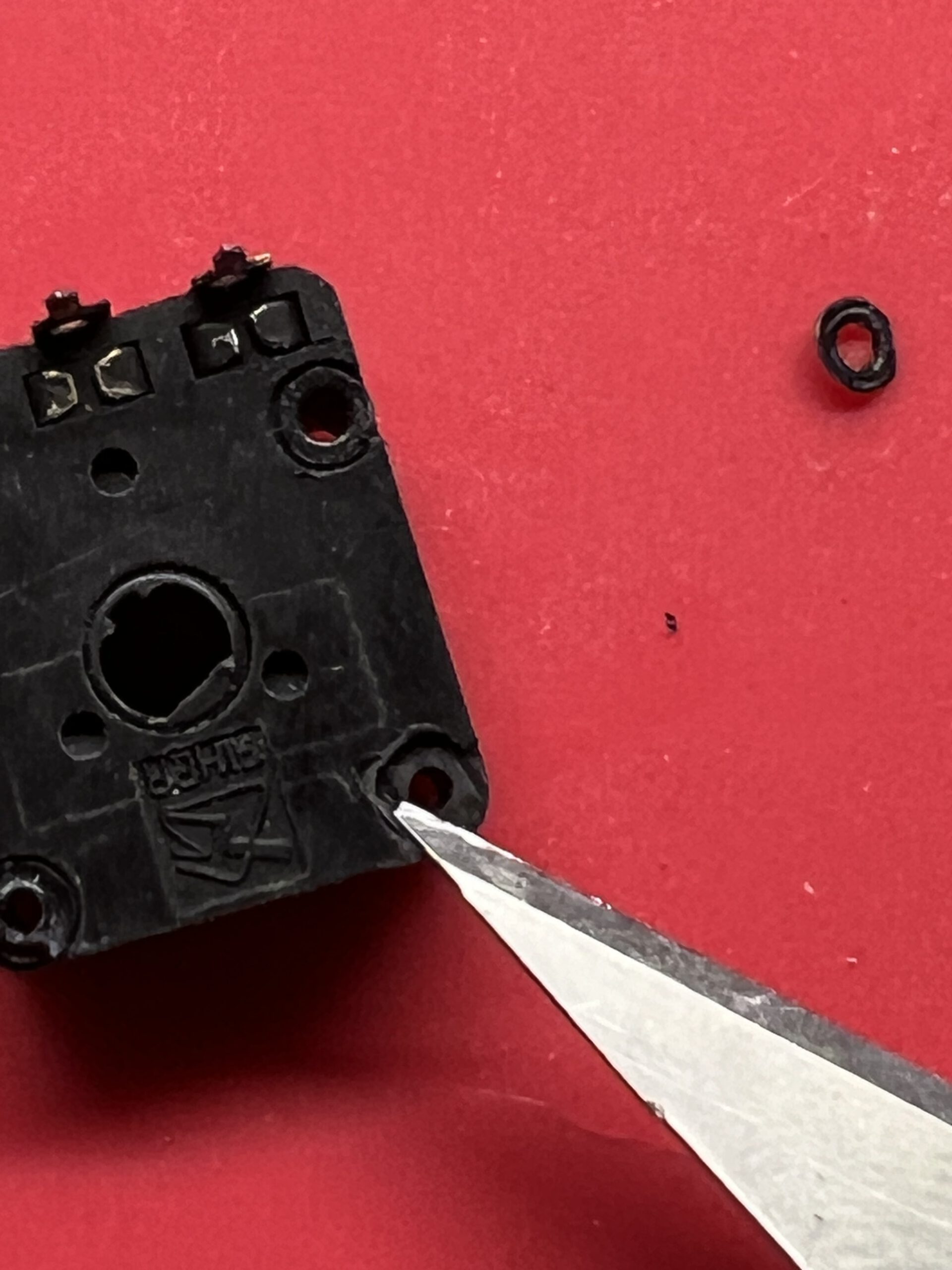

The cover is pressed onto the housing from the bottom and riveted over four plastic pins; you have to cut these slightly with a scalpel, then the cover can be pried open.

With the potentiometer open, do what one does with open potentiometers – clean the wiper and track with isopropanol or mild alcohol, gently bend the wiper contacts back into shape, and – I am grinding my teeth while writing this – apply a little contact oil, if available. Absorb any excess oil, reassemble the potentiometer, solder it back in place, bend the tabs back, and it’s done.

Reassemble everything – and it works.

HackTribe your E2S with a Colab Notebook

Follow-up to the post on the Hacktribe firmware project for the Electribe 2:

Colab Notebook as online step-by-step tutorial doing all the work – no need to install Python

Want to have a Hacktribe, but don’t want to install Python? You can use this Notebook – which you can run on a virtual Python environment provided by Google, called Colab. It creates a modified firmware file with Bangcorrupt’s scripts, as well as modified sample and pattern files from the existing samples and patterns on your Electribe Sampler.

Additional Python script to adapt sample bank AND pattern bank to the HackTribe firmware

There is also a new Python script the notebook uses, but which you can also run locally on your machine: It takes an e2sSample.all sample dump file, and a matching .e2sallpat pattern dump, and adapts them to the HackTribe by moving all samples to User sample space. The patterns are then modified to find the samples in their new locations.

You can find and download the script in my repository here.

Documentation

In writing the script, I had to document parts of the sample dump file. bangcorrupt did not want to have documentation as part of the main hacktribe repository to be on the safe side of hacking/reengineering regulations, so I created a separate documentation repository. It’s quite empty so far.

Did you know that those rotary switches from Minimoog and Co. can be configured?

That you can change a three-position switch into one with up to eleven positions?

I didn’t. Continue reading

Yay! I’ve bought a DIY Minimoog. (And Jenny is going to love it!)

Isn’t it GORGEOUS? Classic Minimoog – less of a control panel, more of an erogenous zone for synth nerds. Tell me you don’t want to feel up these knobs! The pure beauty of a one-of-a-kind electronic instrument. The design and the sounds are still in highest demand more than 50 years after its design – and I was pretty sure I’d never, never even be tempted to buy one.

I never even wanted a Minimoog!

Let’s be honest: Moogs are ludicrously overpriced, and overhyped. Not a single classic Moog ladder filter sound you couldn’t do just as well with a modern plugin, or almost any modern hardware. Hey, even the R3 – my most underdog synth – can do pretty decent Moog impressions. And if you are with the “Digital-will-never-sound-like-true-analog” esoterics, there is still the option of Neo Old School: Using the old design with the upsides of modern analog technology. Get yourself a Boog, for fuck’s sake. (And a life.)

Still… as we know, it’s all about the workflow – and about that unique combination of how an instrument looks, feels, and sounds. So when I saw a Moog enclosure and front panel on eBay for a couple of Euros, I could not resist and had to buy it.

“It’s aliiiiive!” – How to give life to an empty corpus

Repairing your Macbook Air M1 (2020) if the trackpad does not click

Suddenly, the Mac did no longer click with me: The trackpad in my MacBook Air M1 (end-2020) no longer clicked, seemed to have jammed, gave no haptic feedback. I could no longer click any objects on the screen; without an external mouse, the laptop was unusable.

It was quite easy to solve that problem; some short notes might help you if you have a similar problem.

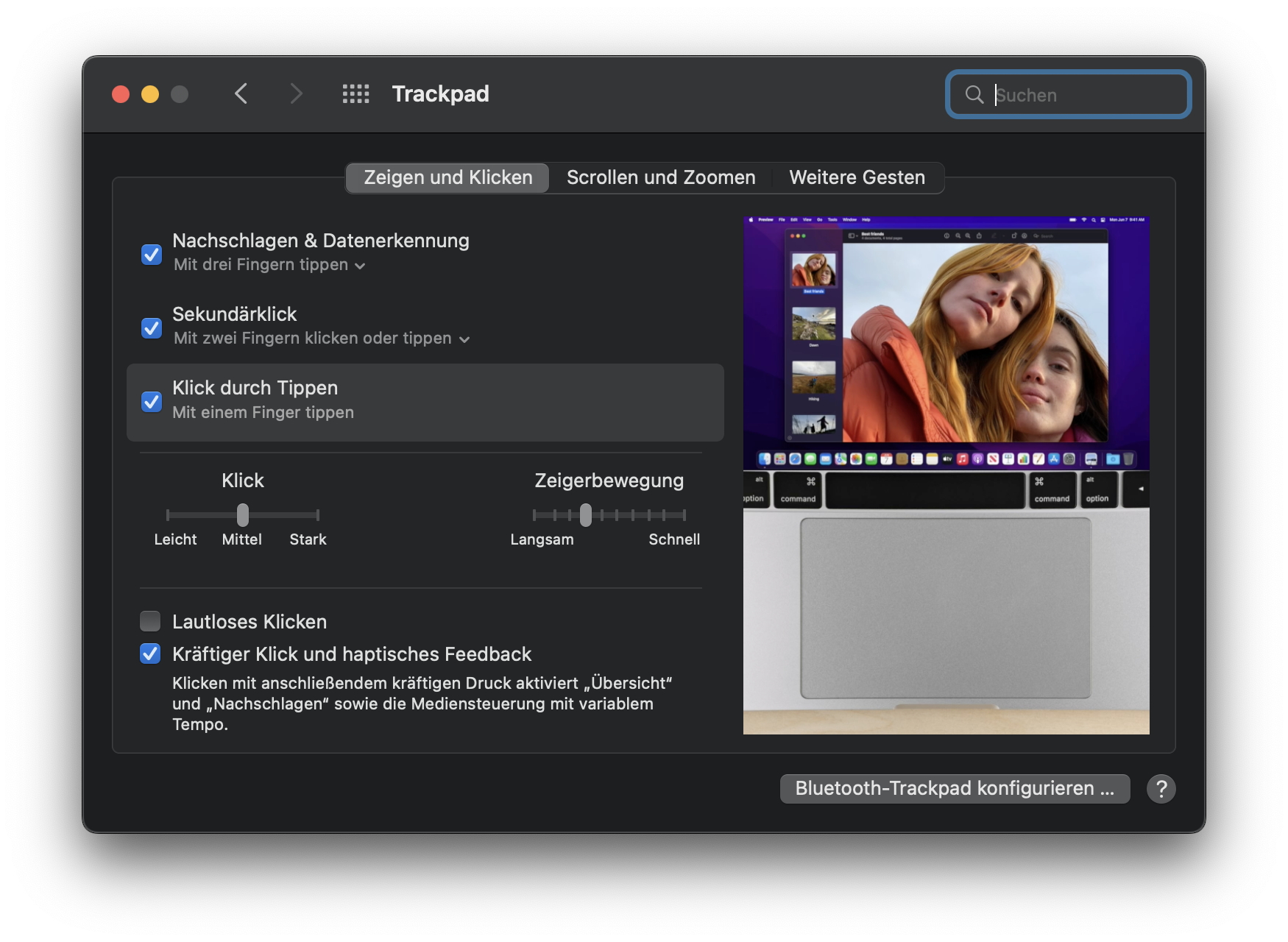

- Fast fix: Activate “Tap to click”. Get a mouse and go to the Trackpad settings and set “Tap to click”. At least you can use the trackpad now with selecting things bei tapping them instead of clicking them.

- It might not be the hardware’s fault. I did not realize it at once, but the click you feel when you click the trackpad is not produced by a mechanical spring but by activen electric components – a couple of small electro magnets producing the haptic feedback. This post by pocket-lint.com does a good job explaining the techonology. This means that it might actually a firmware or OS problem. I read that some people had success temporarily disabling all haptic feedback settings; give it a try.

- It is quite possible to replace the trackpad if necessary. It is not really easy to take a modern Apple device apart, but it is feasible, provided you have the right tools. Remember that Apples patronizing “Genius Bar” technicians might charge you heavily. But: get the tools!

- The right tools for fixing a Macbook Air. You will need them. I had Torx bits for mobile phone screws anyway and bought some more on Amazon. This is what you need:

- a Pentalobe-P5 screwdriver for Apples 5-star-hole housing screws

- a Torx-T4 screwdriver for removing the trackpad cable connector clamp

- a Torx-T5 screwdriver for the trackpad screws

- a magnifying glass

- pincers

- a box with several compartments to keep the 6 different types of screws apart and safe

- good workplace conditions – proper lighting, enough space, a workplace mat

- Taking the Air apart, step by step. ifixit does a brilliant job at explaining and showing every step – have the tutorial on a second screen next to your workplace so that you can look at every step when you need it. Pro tip: Read every step thouroughly before you do it – I didn’t at one point and missed that there are distance shims on top of the trackpad which drop to the floor when you take it out. Some rather undignified crawling ensued.

- Apple supports your Right to Repair. Seriously. A little bit. „Right-to-repair“ laws have forced Apple to move. If you insist on trying to repair your iDevice, Apple gives you information, tools, and parts – provided that the iDevice is rather recent, and that you live in the US. But to be fair: You can find the comprehensive Macbook Air Servide Manual (PDF) for download. You may also order a replacement trackpad for about $100 in the U.S. Apple’s Service Support draws some criticism for its pricing and for its rather complicated procedures, but it is a start.

In short: This is what I did to get the trackpad working again

- Bought the tools.

- Opened the Mac and detached the battery connector. My advice: do that, then reconnect and check whether the trackpad is already working again.

- Took out the trackpad and gave it some menacing looks, carefully poked at the metal strips, and cleaned what seemed worth cleaning.

- Cleaned the trackpad bay in the housing to remove any object that might cause problems

- Reinserted the trackpad. The service manual states that a new trackpad comes with shims in different thicknesses, so I measured the thickness of those I had and found that some were .1mm and some were .15. I inserted the .15mm ones to the front, and the .1mm ones up next to the keyboard.

- Put everything back together. The critical moments: Reconnecting the battery connector with minmal force. Reconnecting the trackpad’s flat cable to the ZIP connector: open, pull out flat cable, reinsert, close locking mechanism. Reconnect the PCB connector plug for the trackpad next to the battery connector.

- Triple-checked the connectors, then attached Macbook to power supply and switched it on. Worked.

Kaffee aus dem Jura

In which I am laying out the reasons for my conviction that the Jura brand coffee machine which I am trying to fix right now is a desaster. German only.